nytimes.com

The F.C.C. voted to dismantle rules that require internet providers to give consumers equal access to all content online. Here’s how net neutrality works

The Federal Communications Commission voted on Thursday to repeal Obama-era net neutrality rules, which required internet service providers to offer equal access to all web content without charging consumers for higher-quality delivery or giving preferential treatment to certain websites.

The vote is a big win for Ajit Pai, the agency’s chairman, who has long opposed the regulations, saying they impeded innovation. He once said they were based on “hypothetical harms and hysterical prophecies of doom.”

These are the rules that were repealed

The original rules went into effect in 2015 and laid out a regulatory plan that addressed a rapidly changing internet. Under those regulations, broadband service was considered a utility under Title II of the Communications Act, giving the F.C.C. broad power over internet providers. The rules prohibited the following practices:

BLOCKING Internet service providers could not discriminate against any lawful content by blocking websites or apps.

THROTTLING Service providers could not slow the transmission of data based on the nature of the content, as long as it is legal.

PAID PRIORITIZATION Service providers could not create an internet fast lane for companies and consumers who pay premiums, and a slow lane for those who don’t

How it could affect you

Many consumer advocates have argued that if the rules get

scrapped, broadband providers will begin selling the internet in bundles, not

unlike how cable television is sold today. Want to access Facebook and Twitter?

Under a bundling system, getting on those sites could require paying for a

premium social media package.

In some countries, internet bundling is already happening.

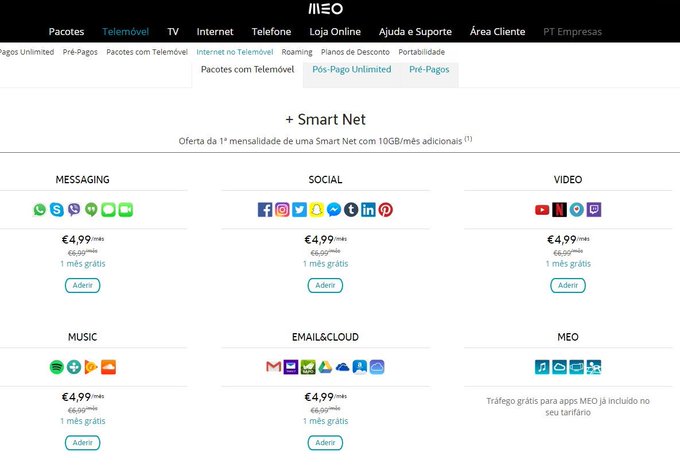

In October, Representative Ro Khanna, Democrat of California, posted a

screenshot on Twitter from a Portuguese mobile carrier that showed subscription

plans with names like Social, Messaging and Video. He wrote that providers were

“starting to split the net.”

Another major concern is that consumers could suffer from

pay-to-play deals. Without rules prohibiting paid prioritization, a fast lane

could be occupied by big internet and media companies, as well as affluent

households, while everyone else would be left on the slow lane.

Some small business owners have also been concerned these

issues will affect them, worrying that industry giants could pay to get an

edge, and leave them on an unfair playing field.

“The internet, the speed of it, our entire business revolves

around that,” David Callicott, who sells paraffin-free candles on his website,

GoodLight, said last month.

E-commerce start-ups, for their part, have feared they could

end up on the losing end of paid prioritization, where their websites and

services load slower than those run by internet behemoths. Remote workers of

all kinds, including freelancers and franchisees working in the so-called gig

economy, could similarly face higher costs to do their jobs from home.

The argument against regulation

“It’s basic economics,” Mr. Pai said in a speech at the

Newseum in April. “The more heavily you regulate something, the less of it

you’re likely to get.”

The F.C.C. chairman has long argued against the rules,

pointing out that before they were put into effect in 2015, service providers

had not engaged in any of the practices the rules prohibit.

“Did these fast lanes and slow lanes exist? No,” he said in

the speech. “It’s almost as if the special interests pushing Title II weren’t

trying to solve a real problem but instead looking for an excuse to achieve

their longstanding goal of forcing the internet under the federal government’s

control.”

Several internet providers have made public pledges in

recent months that they will not, block or throttle sites once the rules were

repealed. The companies argue that Title II gives the F.C.C. too much control

over their business, and that the regulations make it hard to expand their

networks.

The internet was already changed

Perhaps the repeal won’t change the direction of the

internet. In November, Farhad Manjoo argued that the internet has already been

dying a slow death, and that the repeal of net neutrality rules only hastens

its demise.

He wrote that the biggest American internet companies —

Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft — “control much of the online

infrastructure, from app stores to operating systems to cloud storage to nearly

all of the online ad business.”

Meanwhile, most American homes and smartphones connect to

the internet through a “handful of broadband companies — AT&T, Charter,

Comcast and Verizon, many of which are also aiming to become content companies,

because why not.”

No comments:

Post a Comment